By Joseph J. Wadland

On March 14, 1970, Richard Atkinson, a sophomore at Bates College in Lewiston ME, lost his footing during an intramural basketball game and slammed into an unpadded brick wall. He died the next day from head injuries.[1] Bryant Gumbel, the then sports editor of the student newspaper wrote: “[y]et to sit back and say that he smashed into an exposed brick wall less than fifteen feet away, and accept it simply for that, is senseless. As anyone who has been in the Bates gym realizes, the west wall in the gym is brick; it is bare; and it is only about fifteen feet away from the edge of the court. As anyone who has been in any other gym realizes, any walls that close to the court are in almost all cases covered with relatively inexpensive wrestling mats.”

Bryant Gumbel urged that “steps be taken in the immediate future… to rid the gym of the danger of an exposed brick wall… [so] that the next time any accident involving that wall occurs, the writer, whoever he may be, will also be able to say that the athletic department cannot rightfully bear the blame. There are some who will say that Rich was probably the only person to hit that wall in the last fifty years. Maybe so. Whether he was the only one in the last fifty years; or whether he’ll be the only one until that gym crumbles to the ground is unimportant. What is there to lose by gambling some money [on safety improvements] on the chance that one day the money spent may save a life?”[2]

Bryant Gumbel had it right more than fifty (50) years ago. Just ask Matt Wetherbee and Joel Gonzalez. In the span of a mere seven (7) months in 2016-17, at two gyms less than ten (10) miles apart in greater Boston, routine drives to the basket for these two young men in adult recreational basketball leagues turned into life altering plays. Today, Matt and Joel are quadriplegics. Both collided with a padded wall under the basket. In Matt’s case, as he drove to the basket, a defender stepped in, their legs tangled, and he fell headfirst into the wall under the basket. Joel was laying the ball up following a drive from the top of the key. He was fouled as he went up and landed off-balance, and he too struck the wall under the basket headfirst. Both men were young ( 28 and 31 respectively), fit, athletic and seasoned, skilled basketball players. Neither player had sufficient time or distance to avoid or brace for their collision with the wall.

Imagine an NBA game where there is a padded concrete wall, at the point where spectators and media sit in the out-of-bounds area of arenas throughout the country, often no more than 3 or 4 feet from the out-of-bounds line. No owner would permit play to happen, and no player would play and risk his career under such circumstances.[3] Yet this is what happens in thousands of gyms, rec centers and basketball courts throughout the country daily. When a facility has an inadequate buffer zone it creates an unreasonable risk of harm.

Regardless of whether anyone is familiar with the term “buffer zone,” the underlying concept is clear. Basketball actions, plays and player deceleration frequently occur in the out-of-bounds area of the court, whether it is a player attempting to save a loose ball from going out-of-bounds, a player running full speed for a lay-up where his momentum carries him out-of-bounds, or a player who is tripped or fouled near the out-of-bounds line and who loses his balance, forcing him out-of-bounds. In each of these instances, a player requires a safe distance between the out-of-bounds line and the nearest wall or obstruction to prevent against injury. It is important to remember that unlike boards in hockey and outfield walls in baseball, walls in the buffer zone of basketball courts are not part of the sport or in the field of play. They constitute a risk which is not inherent to the game itself.

Matt Wetherbee’s and Joel Gonzalez’s spinal cord injuries were predictable and avoidable. There was no buffer zone under the basket in Matt’s case; the wall was the out-of-bounds marker. In Joel’s case, the wall he struck was approximately 4 feet from the baseline.

Several basketball and sport governing bodies have promulgated standards, guidelines, recommendations and best practices respecting buffer zones. The American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (“AAHPERD”) and the National Intramural-Recreational Sports Association (“NIRSA”) both specify a preferred buffer zone of ten (10) feet and a minimum of six (6) feet. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) specifies a preferred buffer zone of ten (10) feet and a minimum of six (6) feet under the baskets and three (3) feet on the sides. The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) specifies a preferred buffer zone of ten (10) feet and a minimum of three (3) feet. The AAU rule book specifies that the National Federation of State High School (NFHS) rules apply to AAU events (Amateur Athletic Union, 2016). The NFHS also specifies a preferred buffer zone of ten (10) feet and a minimum of three (3) feet.

What is clear from these governing bodies is that the preferred buffer zone distance is ten (10) feet. Even insurers have taken this position publicly.[4] However, many facility owners and operators take the legal position that as long as there is a three (3) foot minimum, they have complied with the standard of care. Alternatively, or in addition, facility owners and operators customarily assert that the risk of danger is open and obvious, players assume the risk of injury and/or are contributorily negligent. They also often will rely on written waivers as a risk management tool, arguing that a player who has signed one has waived his right to bring claim for his injury.[5]

There is no indication by any of the above-referenced organizations or in any of their publications as to how each arrived at its buffer zone requirement/recommendation. A review of the literature turned up no professional article advocating for a three (3) foot buffer zone. According to experts in the field, the three (3) foot minimum incorporated into some of the above-referenced literature is outdated guidance that has been rejected as inadequate by virtually all professionals in the field “for at least the last 50 years.” [6]

The only publication to this author’s knowledge which takes into consideration human biomechanics in establishing buffer zone distance requirements under a basket is an architectural design reference source book entitled “Human Dimension & Interior Space: A Source Book of Design Reference Standards” (1979). It recommends 7.5 to 9.6 feet of buffer zone from the end line under a basket to any obstruction, and as it notes “[i]n sports where the action is more intense, such as basketball, the lack of adequate safety zone clearances may cause injuries to the players and may even prove fatal (p. 257). Another architectural design reference, Architectural Graphic Standards (12th Ed.), also known as the architect’s bible, recommends a ten-foot minimum buffer zone.

A study conducted by Gil Fried and other researchers at the University of New Haven using player measurements, surveys and physics attempted to identify what is an appropriate basketball court buffer zone. Based on the results of physics modeling in the study, the average distance necessary for players to stop their movement safely was reported to be 7.74 feet. The researchers then conducted a simulated game, and the players left the court under the baskets 19 times, traveling on average 5.18 feet. According to the researchers, the physics model theoretically provides the minimum safe buffer zone distance and provides a conservative measurement to provide safer basketball courts. The study concluded that the outdated three-foot minimum buffer zone is not only an arbitrary number but is also unsupported by any scientific research. The researchers concluded that by adopting preferably an 8-foot buffer zone (physics modeling) and at least a 5.2-foot buffer zone (simulated game), facilities can provide a safer distance for players. The study did not try to establish a minimum or uniform standard of care nor purport to be statistically valid.[7]

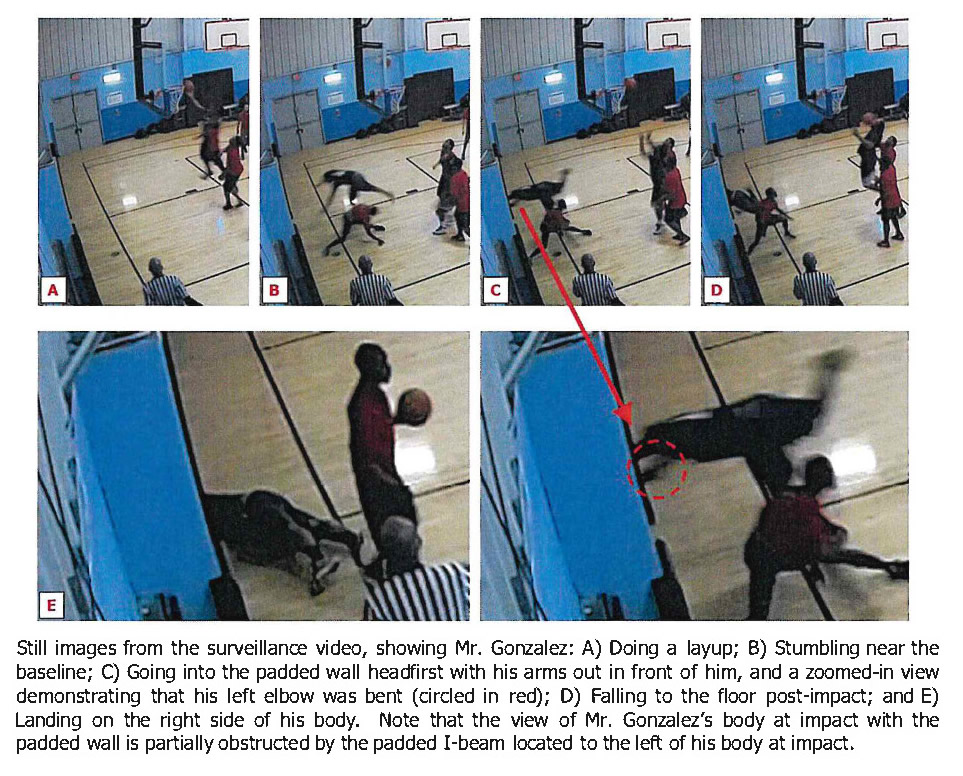

Joel Gonzalez’s injury was captured on surveillance camera video footage (shown below).

A frame-by-frame analysis performed by Wilson C. Hayes, Ph.D. and Erik D. Power, P.E. of Hayes & Associates of Corvallis, OR is included below. While it may be disturbing to watch the video, sport facilities owners/operators, risk managers, athletic directors and others who have responsibility for the safety of sports facilities need to see it, as do insurers and officers of the above-referenced sport governing bodies.

All new facilities should be designed with at least a ten-foot buffer zone. Many existing gyms and courts with less than the preferred ten-foot distance can almost always adjust their baskets and move them in, i.e., shorten the court a few feet on each end with a new baseline, and have a significantly larger and safer buffer zone at least under the baskets.[8] While shortening an already small court may be less than ideal, is not changing it worth avoiding a spinal cord injury or fatality? Further, going forward, juries are unlikely to buy either the ostrich defense (“a freak accident”), accept the 3-foot minimum as an acceptable standard of care or be willing to find a player assumed the risk. Players and consumers generally are unaware of standards or about the potential for such devastating injuries. Juries are more likely today than ever to hold owners/operators accountable for unsafe buffer zones.

\It is important to recognize that for there to be real and effective change across the country in the thousands of gyms with unsafe buffer zones, it must come from the liability insurers and sport governing bodies. So long as a sport governing body such as the NCAA or the NFHS allows games to be played on courts with 3-foot buffer zones and insurers are willing to insure the risk, there will continue to be unnecessary fatalities and spinal cord injuries.

Putting aside the law and insurance, as a sports facility owner/operator, do you want to be the one with a spinal cord injury or fatality on your watch? Stated otherwise, would you prefer to have a reasonably safe facility or rely on the legal doctrines of assumption of risk, comparative fault and/or waiver to try to insulate yourself from liability for an unsafe facility? Which is the responsible approach?

Matt Wetherbee and Joel Gonzalez want you to know that as life-long basketball players, it never occurred to them that they could suffer such a devastating injury playing basketball. They want to prevent what happened to them from occurring in the future. They are the motivation for this article. They refuse to let their quadriplegia define their lives. They both are active in raising awareness about spinal cord injuries, research and promising, yet still unsuccessful, treatments. Matt Wetherbee has started the MW Fund, a non-profit which awards scholarships to spinal cord injured patients to assist in their rehabilitation. To read more about Matt and his story, go to www.mwfund.org.

Matt’s and Joel’s accidents were the subject of litigation which is beyond the scope of this article. The Massachusetts Trial Court maintains a website for electronic case access, deemed to be public information: www.masscourts.org/eservices/home.page.2. The civil action caption and docket number for each case is: Gonzalez, Joel vs. Morton, James O’S., et al, Suffolk Superior Court Civil Action No. 1884CV00690 and Wetherbee, Matthew H., vs. Cambridge Racquetball, Inc., et al., Middlesex Superior Court Civil Action No. 1681CV02072. The author of this article represented both Mr. Gonzalez and Mr. Wetherbee.

Joseph J. Wadland of the Massachusetts firm, Wadland & Ackerman, is a trial attorney with over 35 years’ experience. He represents both plaintiffs and defendants as well as insurance carriers. For more information, see www.wadlandackerman.com.

[1] Bates College, “The Bates Student- volume 96 number 20- March 21, 1970,” at p. 1. (1970). The Bates Student. 1593.

[2] Id., p. 10.

[3] YouTube is replete with videos of NBA players going out-of-bounds and colliding with fans, chairs and other obstructions. For example, LeBron James chased a loose ball out-of-bounds and collided with golfer Jason Day’s seated wife in 2015, injuring her. The YouTube video as well as Sports Illustrated still shots, show Lebron going headfirst when he struck her. Compare this with the video footage of Joel Gonzalez’s injury, infra – showing his head-first position immediately before striking the wall. The two are very similar. Now imagine a concrete wall rather than Mrs. Day at the point of impact for Lebron.

[4] See “Basketball Court Tech Sheet,” Employers Mutual Casualty Company (2011), stating that “basketball courts should have a minimum clearance of 3 feet around the perimeter of the playing court, but 10 feet is highly recommended.”

[5] Sports facilities owners/ operators and risk managers often use waivers or releases as a means of limiting their liability and exposure. But a waiver/release should not be the first line of risk management for an unsafe facility. In Massachusetts for example, its version of the model Health Club Services Contract Act (Mass. Gen. Laws Chapter 93, Section 78, et. seq.) outlaws use of waivers or releases by a health club or fitness facility and constitutes a violation of the Massachusetts Consumer Protection Act. Insurers of health clubs in Massachusetts who require their insureds to use waiver language in their contracts with consumers expose themselves and their insureds to treble damages and an award of attorney’s fees. Several other states have their own iterations of the model Health Club Services Contract Act.

[6] See, e.g., “Injuries in the Buffer Zone: A Serious Risk Management Problem.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, Vol. 78 No.2 (Neil Dougherty and Todd Seidler).

[7] “Buffer Zone: Policies, Procedures, and Reality.” Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, 2019, 29, 86-101(Ceyda Mumcu, Gil Fried and Dan Liu)

[8] According to Hayes & Associates, another approximately 18 inches of buffer zone space likely would have avoided Joel Gonzalez’s spinal cord injury.