By Paul J. Greene & Matthew D. Kaiser, Global Sports Advocates

La’el Collins, an offensive tackle for the Dallas Cowboys, sued the NFL, the NFL Management Council, and Roger Goodell on October 6, 2021, for breach of contract and fraudulent misrepresentation after an arbitrator under the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement (“CBA”) upheld the NFL’s 5-game suspension against Mr. Collins for violating the drug testing requirements of the CBA’s Policy and Program on Substances of Abuse (the “Policy”). In his complaint, Mr. Collins also sought a preliminary injunction to enjoin the NFL from imposing the 5-game suspension while the case was being appealed. Although District Court Judge Amos L. Mazzant was critical of the arbitrator’s decision to uphold the suspension and noted he personally would have imposed only a fine against Mr. Collins, Judge Mazzant ultimately dismissed Mr. Collins’ request for a preliminary injunction because of the significant deference district courts must give to final arbitral decisions arising out of CBAs.

In March 2020, the NFL and NFLPA agreed to a new 10-year CBA. As part of the CBA, players consented to be bound by the Policy, “which includes provisions for mandatory testing for prohibited substances, treatment protocols for players that use substances of abuse, and discipline for violations”.[1] There are 9 different substances of abuse under the Policy, one of which is THC (marijuana), which is specifically tested for between the start of the pre-season training camps and the club’s first pre-season game.[2]

If a player tests positive for THC (or any of the other 8 substances of abuse), the player automatically enters Stage One of the Policy’s Intervention Program. In Stage One, a player is required to fulfill a treatment plan that addresses his substance of abuse issues. Unless unusual and compelling circumstances arise, a player will only remain in Stage One for a period of less than 60 days. If the player is found to need specific clinical intervention or treatment, the player is advanced to Stage Two, where a more stringent treatment plan and clinical intervention are provided. All players in Stage Two are subject to unannounced testing and will remain in Stage Two until discharged by the medical director.[3]

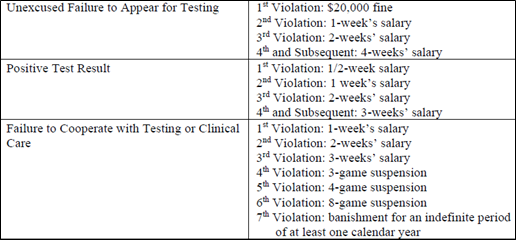

Under the Policy, a player in Stage Two who has a positive test (which can include a variety of situations such as providing a diluted specimen or failing to cooperate fully in the testing process), fails to appear for testing without adequate reason, or fails to cooperate with testing, will be subject to discipline by the Commissioner as set forth in Section 1.5.2(c) of the Policy:

However, under Section 1.3.3, “additional discipline” can be imposed if a player deliberately tries to substitute or adulterate a specimen, alter a test result, or engage in prohibited doping methods.[4]

Before the close of the 2019 season, Mr. Collins had advanced to Stage Two of the Intervention Program. During the following offseason, Mr. Collins provided incorrect or incomplete whereabouts information multiple times and on at least three occasions failed to fully cooperate with the testing process. As a result, the NFL imposed a 4-game suspension on Mr. Collins, but following Mr. Collins’ decision to appeal the sanction, the NFL and Mr. Collins reached an agreement whereby Mr. Collins would pay a fine of $478,470 and remain in Stage Two of the Intervention Program in lieu of serving the 4-game suspension (the “4-Game Settlement Agreement”). As noted in the 4-Game Settlement Agreement, neither party was allowed to use the 4-Game Settlement Agreement “as precedent in any other proceedings, except as required or necessary to enforce its terms.”[5]

Following the conclusion of the 4-Game Settlement Agreement, Mr. Collins tested positive under the Policy on multiple occasions and on at least three other occasions also failed to appear for testing. The NFL deemed both the positive tests and failure to appear for testing as first violations and imposed the corresponding penalties as set out in the rigid sanctioning chart in Section 1.5.2(c): $20,000 fine for his unexcused failure to appear for testing and another fine of 1/2-week salary for his positive test results.

Months later, Mr. Collins failed to appear for several toxicology appointments and on one occasion, when he did appear for testing, he asked the collector if there was something that “we could do” and offered the collector $10,000. He subsequently failed to appear for testing on a number of occasions the following month.

On January 6, 2021, the NFL assessed Mr. Collins’ case and imposed a 5-game suspension, which was upheld on appeal. The arbitrator found Mr. Collins’ attempt to bribe the test collector was an attempt to evade or avoid testing, meaning Mr. Collins was “subject to the discipline set forth in Section 1.3.3 of the Policy”.[6] The arbitrator found a 5-game suspension was a reasonable punishment under Section 1.3.3 since such a punishment was the “next logical progression from prior discipline”.[7] Mr. Collins subsequently appealed this decision to state court in Texas, which was later removed to federal district court, and sought a preliminary injunction to prevent the 5-game suspension from being enforced until after the case was decided.

In order to obtain a preliminary injunction, Mr. Collins needed to prove 4 elements: (1) a substantial likelihood on the merits, (2) irreparable harm, (3) the harm he would suffer by being suspended outweighs any potential injury the NFL may suffer if the preliminary injunction was granted, and (4) the public interest supports granting an injunction.

Under the first element, Mr. Collins argued he would likely succeed on both his breach of contract and fraud claims because the NFL failed to sanction him as specifically outlined according to the Policy (i.e., he should have only been fined as opposed to suspended) and the NFL made misleading assertions to the arbitrator that he had been suspended for 4 games previously, which the arbitrator relied on in upholding the 5-game suspension against Mr. Collins.

In assessing Mr. Collins’ likelihood of success, District Court Judge Mazzant explained that the court’s review of an arbitrator’s decision is extremely deferential: as long as the arbitrator imposed a sanction that can be arguably construed from the Policy (i.e., “rationally inferable”[8]) and did not fashion “his own brand of industrial justice”[9], then the District Court would not have the authority to reconsider the merits of the arbitral award and could not set aside the award, even if the award was based on factual errors or on misinterpretation of the CBA. Such deference is required because the parties to the CBA “have bargained for the arbitrator’s” – not the court’s – “construction of their agreement.”[10]

Under this deferential legal standard, even though District Court Judge Mazzant had “serious concerns regarding … the arbitrator’s interpretation of the [P]olicy”[11] and actually thought the arbitrator’s interpretation of the Policy was incorrect (i.e., contrary to the arbitrator’s findings, “the NFL did not give itself authority under [the Policy] to subject a player to suspension as a type of ‘additional discipline’ for deliberately evading or avoiding testing”[12]), he determined the arbitrator’s belief that a 5-game suspension was an available sanction could arguably be construed from the Policy. Consequently, District Court Judge Mazzant found Mr. Collins could not prove he would succeed on the merits.[13]

Additionally, even though the District Court Judge Mazzant also had serious concerns with the NFL’s conduct during the arbitration proceedings, namely, the NFL’s use of the 4-Game Settlement Agreement to support its position to ban Mr. Collins for 5-games (an act that was in direct contravention to the terms of the 4-Game Settlement Agreement), Judge Mazzant similarly found Mr. Collins could not prove a likelihood of success on the merits under this claim because Mr. Collins was actually written up for a 4-game suspension and the settlement agreement was given to the arbitrator to review, meaning the arbitrator was not duped by the NFL.[14]

In dicta, District Court Judge Mazzant went through the other three prongs of the preliminary injunction standard and similarly found Mr. Collins failed to prove each of them, too. As a result, Mr. Collins’ motion for a preliminary injunction was dismissed even though the Court made clear that it took “no comfort in enforcing an arbitration award that upholds a punishment that, arguably, is not permissible under the parties’ CBA.”[15]

[1] Collins v. NFL, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 196329, *2 (E.D. Tex. 2021).

[2] See, National Football League Policy and Program on Substances of Abuse, 2020, p. 7.

[3] Id. at p. 12-14.

[4] Section 1.3.3 states:

“A Player who fails to cooperate fully in the Testing process as determined by the Medical Advisor or provides a dilute specimen will be [*19] treated as having a Positive Test Result. In addition, a deliberate effort to substitute or adulterate a specimen; to alter a test result; or to engage in prohibited doping methods will be treated as a Positive Test and may subject a Player to additional discipline.”

See, id. at p. 14.

[5] Collins, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 196329, *17.

[6] Policy, supra, at Appendix E, p. 28.

[7] Id. at *7.

[8] Id. at *13.

[9] Id. at *9.

[10] Id. at *21.

[11] Id. at *17.

[12] Id. at *20.

[13] District Court Judge Mazzant agreed with the arbitrator that, pursuant to Appendix E of the Policy, the arbitrator had to apply the discipline set forth in Section 1.3.3 since the arbitrator found Mr. Collins attempted to evade or avoid testing when he tried to bribe the test collector with $10,000. However, the sanction for “evading or avoiding testing” was not explicitly noted in Section 1.3.3. Thus, while the arbitrator believed such conduct fell within the ambit of the second sentence in Section 1.3.3, which allowed the arbitrator to impose “additional discipline” beyond Section 1.5.2(c), District Court Judge Mazzant believed Mr. Collins’ evasion or avoidance to get tested should have been treated as a failure to cooperate fully in the testing process and thus fell within the first sentence of Section 1.3.3, which would have precipitated only a fine under Section 1.5.2(c).

[14] Id. at *28-29.

[15] Id. at *35.