By Joseph Sabin, Southeastern Louisiana University; Andrew L. Goldsmith, Colorado State University; Caroline G. Fletcher, Troy University; Sarah Stokowski, Clemson University; and Michael S. Carroll, Troy University

Abstract

Gender discrimination within collegiate sport has made it difficult for women to obtain coaching and administrative roles. Federal legislation – including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Equal Pay Act, and Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 – has helped combat gender discrimination in many facets of society, including sport. Although significant progress has been made regarding athletic opportunities, which has increased sport participation rates among girls and women, a wide disparity persists in the areas of coaching and athletic administration. This paper strives to explore employment discrimination in intercollegiate athletics through a review of relevant legal cases.

Gender Employment Discrimination in Intercollegiate Sport: A Review of Case Law

In the United States of America (U.S.), laws (e.g., Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972) have been put into place to combat gender-based discrimination. While gender discrimination exists in many professions, it particularly is salient within the sport setting, largely because sport historically is a male-dominated space. Women consistently are held to different expectations (i.e., double standards; Buzuvis, 2010) and are not paid equally to their male counterparts (Bass, 2016), ultimately leading this population to be overlooked for a variety of positions due to their gender (Hardin & Whiteside, 2012).

Within the intercollegiate sport setting, specifically among National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) member institutions, the lack of female representation is staggering. In 2016, 59.8% of head coaches for women’s sports were male (Wilson, 2016). In 2017-18, women accounted for 40.1% of head coaching jobs in Division I for women’s sports, but only 4.0% of female head coaches were represented within Division I men’s programming (Lapchick, 2019). Considering men (in both men’s and women’s intercollegiate sport) hold most head coaching positions, steps need to be taken to ensure that employment opportunities, pay, and benefits are equitable for women.

Arnold et al. (2015) urged sport educators to teach the next generation of students to challenge male hegemonic ideology and celebrate the women who have gone where previous women were not allowed nor welcome. “These types of negative cultural norms in sport journalism and broadcasting must be stopped and changed so that true gender equality can be achieved one day soon” (Arnold et al., 2015, p. 41). Similarly, Weatherford et al. (2018) recommended that male sport leaders become allies for women in sport, promoting women into positions of power to reflect society. Refusing to support women leads to gender discrimination, stymies progress, and continues to marginalize women (Weatherford et al., 2018). Given that the NCAA (2020) strives for “gender equity among…athletics department staff” (p. 2), steps must be taken to better understand gender discrimination in the collegiate sport space.

Introduction

U.S. President John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act (EPA) in 1963, which requires equal pay for equal work and prohibits employers from paying men and women “… different wages or benefits for doing jobs that require the same skills and responsibilities” (“Equal Pay Act,” 2017, para. 1). The EPA amended the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established minimum wage, overtime pay, and child labor standards influencing full-time and part-time workers in both the private and government sectors (“Wage and Hour Division,” 2016). The EPA involves any type of payment, including salary, overtime, bonuses, stock options, life insurance, vacation, holiday pay, and benefits (“Equal Pay Act,” 2017), as well as contract length.

The EPA was among the first federal laws to challenge gender discrimination. It is important to reference the EPA due to the pertinence the legislation plays in regard to coaches’ salary discrepancies. Specifically, the EPA may assist in: (a) determining whether the jobs are substantially equal; (b) determining if the salary discrepancy is based on the gender of the team and not the gender of the coach; (c) revenue production by men’s team compared to that of the women’s team; (d) determining if the men’s coach has extra responsibility; and (e) the market force defense (Fenton, 1998).

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination. Title VII of this landmark civil rights and labor law forbids discrimination in the workplace based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Most claims regarding employment discrimination fall under Title VII. However, if the claims of employment discrimination occur in educational institutions receiving federal funds, such claims can be made under Title IX. Title IX (2018) prohibits federally funded educational programs from discrimination based on sex. Congress enacted Title IX to combat the increasing occurrence of discrimination against women in the educational realm. Student-athletes’ participation opportunities, athletics scholarships, and other treatment and benefits claims often are made under Title IX (Chamberlain, 2018). Thus, Title IX protects collegiate athletics employees from gender-based discrimination.

While Title IX has helped women within sport, it has not lived up to its potential for change. Since its implementation, female head coach and athletic director numbers have decreased substantially. Women hold around 23% of all NCAA head coaching, athletic director, and conference commissioner positions (NCAA, 2016). According to the NCAA (2016), in 2015-16, women made up 19.6% of athletic directors, consisting of approximately 222 women for 1,135 positions. Among head coaches in women’s sports in 2011, only 42.6% were female. This could be rationalized if women were equally represented in men’s sports. However, females made up less than three percent of head coaches in men’s sports (Acosta & Carpenter, 2016; Wilson, 2016). Essentially, men consume many university coaching positions, even in women’s sports.

Geno Auriemma, the head women’s basketball coach at the University of Connecticut (UConn), arguably is the most successful coach in women’s basketball and leads the winningest women’s basketball team in the country. Auriemma, an 11-time national champion, signed an extension in 2017 valued at $13 million dollars over four seasons. Around the same time, UConn men’s basketball coach Kevin Ollie signed a similar extension, but with a heftier price tag valued at $17.9 million dollars. Ollie’s contract came on the heels of a 2014 NCAA national title, his first and only at UConn. Ollie’s extension emanated just five seasons into his tenure with the Huskies. After the 2016-17 season, Ollie had compiled a 113-61 record, which included one losing season in 2016-17. Auriemma, on the other hand, amassed a 187-6 record in the same time span, which included four consecutive national championships from 2012-2016, two undefeated seasons, and a record 111-game winning streak. Again, the pay discrepancy is due in large part to men’s basketball being a revenue-producing sport, while women’s basketball, even for the highest-caliber teams, is not (Bigelow, 2019; Doyle, 2017). In 2012, the median head coach salary at NCAA Division I FBS institutions for men’s teams was $3,430,000 compared to $1,172,400 for women’s teams, a difference of roughly $2.3 million (Gentry & Alexander, 2012).

During the 2015-16 season, University of South Carolina (USC) head women’s basketball coach Dawn Staley became the first women’s coach in school history to earn $1 million per year (Cloninger, 2015). Staley has been at USC for 11 seasons and has a 273-97 overall record with four Southeastern Conference (SEC) tournament championships, seven NCAA tournament appearances, and a 2017 national championship. Her counterpart, head men’s basketball coach Frank Martin, has been with the Gamecocks for seven seasons and has a 129-106 record, including one NCAA semifinal appearance in 2017. Martin makes more than double Staley’s salary, $2.45 million (Cloninger, 2016).

Barrett et al. (2018) explored the experiences of female athletic trainers providing care to male athletic teams at the collegiate level. According to National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) statistics, 54% of members are women. However, only a small number of female trainers provide care to male sports teams at the professional or college level (Barrett et al., 2018). The potential long-term implications to this issue are paramount. This especially is germane to female athletic trainers, as they are less likely to work with male sports teams. As such, they miss out on or are passed over for career opportunities working for male professional sports teams, which can greatly hinder upward mobility within their profession. Further, it should be noted that because there are more professional men’s sports teams, more opportunities for male athletics trainers exist.

Female athletic trainers interviewed in the Barrett et al. (2018) study experienced discriminatory behavior, sexism, and gender bias in their respective workplaces. “The reasons are multifactorial, including traditional sex stereotyping and the social networking of male leaders” (p. 113). Participants also reported experiencing double standards. For example, when female athletic trainers act professionally and exercise their decision-making abilities (e.g., not clearing a male athlete to participate due to injury), they are perceived negatively and sometimes referred to as a “bitch” (Barrett et al., 2018, p. 113).

Several theories present explanations for the disconnect between female athletic trainers and male sports teams. These theories or reasons include possible sexual harassment, discrimination, bullying, work-life balance, social networking (e.g., “Ole’ Boys’ Club”), and traditional gender role stereotypes. Barrett et al. (2018) cited evidence of female athletic trainers being prone to experiencing harassment, discrimination, bullying, and work-life balance issues in college athletics; however, “… no direct link has been made to these issues and the experiences of women athletic trainers working with male sport teams” (p. 114).

To achieve gender equity and fulfill the mission of the NCAA (2020) and its membership institutions, it is important to examine the issue using relevant case law. The following section presents relevant case law discussion on prominent Title IX lawsuits and the resolutions after filing. Such cases can help those in decision-making positions to look at precedence and ensure federal legislation is followed.

Application of Title IX in Employment Discrimination

Unlike Title VII and the Equal Pay Act, the plain language of Title IX does not appear to apply directly to employment discrimination, stating that “… no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance…” (“Title IX,” 2018). In North Haven Board of Education v. Bell (1982), the United States Supreme Court unequivocally interpreted Title IX to provide protection from gender discrimination not only to students, but also to employees of educational institutions receiving federal funds.

Further, a lesser-known provision of Title IX (20 U.S.C. §1682) allows federal agencies to create regulations to ensure that institutions adhere to Title IX’s mandate. Pursuant to this provision, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights promulgated a number of regulations specifically aimed at employment discrimination, which frequently are referred to as “subpart E” (34 C.F.R. §§ 106.51-106.62). Most relevant to the issue of pay disparity between men’s and women’s coaches is 34 CFR § 106.54, which provides that an institution cannot make distinctions in the rates of compensation on the basis of sex, nor can institutions make or enforce any policy that results in the payment of wages to employees of one sex at a rate less than that paid to employees of the opposite sex.

While these regulations would appear to be a useful tool for coaches of women’s teams pursuing pay commensurate with their men’s team counterparts, the courts have not seen it this way. This is in part due to any alleged discrimination being based on the gender of the athletes, as opposed to the gender of the employee. Proving gender-based employment discrimination on these grounds would require proof that a similarly situated male coach of a women’s team received more compensation. Arguments surrounding compensating those who coach women’s teams far less than their men’s team counterpart as discriminatory for the athletes have failed to persuade the courts as well. Particularly illustrative of this matter is Deli v. University of Minnesota (1994), wherein the court relied on a policy interpretation from the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) that stated differential compensation of coaches only violates Title IX if it deprives female athletes of an equivalent quality of coaching. In order to prevail on a Title IX claim, such an interpretation essentially would require the coach of a women’s team to argue that they are not able to provide high-quality coaching to their players because of their level of compensation. Interestingly, policy interpretations of Title IX issued by the OCR, such as the one relied upon in the Deli case, tend to change and evolve whenever a new Secretary of Education is appointed. It is then reasonable to surmise that it is possible recently confirmed Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona may interpret the issue differently.

Relevant Cases

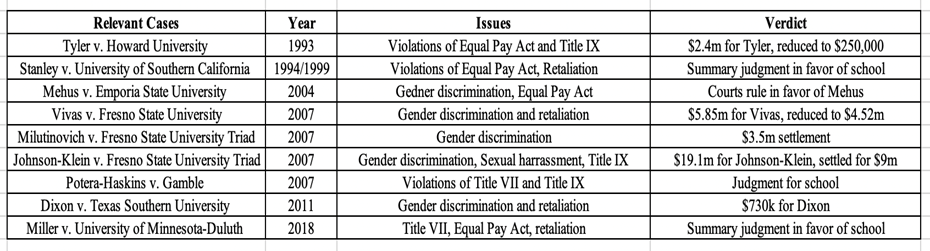

Table 1

Review of Relevant Cases

Tyler v. Howard University

Former Howard University women’s basketball coach, Sanya Tyler, sued the university after the men’s basketball coach, Alfred Beard, was hired with a four-year contract, a leased car, and an annual salary of $78,500. Beard’s qualifications included a stint as an assistant coach for the New Jersey Nets and a 10-year career as a player in the NBA. Tyler was employed by Howard in 1975, became a part-time assistant coach in 1980, and later became the Associate Athletic Director in 1986. Until 1991, Tyler earned roughly $62,000 annually for both jobs. In 1991 she requested a promotion to full-time women’s basketball coach and was offered the position with a salary of $44,436. Consequently however, Tyler would be unable to continue her role as Associate Athletic Director and therefore no longer receive a salary from that position, effectively creating a sizeable pay cut for Tyler.

During her tenure as a head coach, Tyler’s teams won five conference championships and earned one NCAA post-season appearance. Tyler argued that coaching the men’s and women’s teams were substantially similar jobs, a common theme in this type of litigation, alleging that Howard paid disparate wages for equal work. Howard’s defense centered largely around the fact that the jobs were not substantially similar because the men’s coach, in addition to coaching the team, was responsible for generating revenue, which creates increased pressure and accountability. The jury found Howard’s arguments unpersuasive as, after just two hours of deliberation, they returned a verdict in favor of Tyler for $2.4 million, which notably included $138,000 in lost wages due to unequal pay (Fenton, 1998). A judge later reduced the award to $250,000, finding that Howard did not violate the Equal Pay Act and only violated Title IX. (Tyler v. Howard University, 1993).

Stanley v. University of Southern California

This case provides an in-depth analysis of what is colloquially known as the “market forces defense” for the disparity in pay between coaches. Marianne Stanley, then the University of Southern California (USC) women’s basketball coach, experienced a successful tenure at the helm of the Trojans, as she won almost 60% of her games and led USC to three straight NCAA Tournament appearances. When her contract expired, Stanley sought equal pay to her counterpart, men’s basketball coach George Raveling, who posted a 99-103 record in his seven-year career at USC. Stanley and USC were unable to come to an agreement despite the fact that the school offered to raise Stanley’s annual salary from $62,000 to an average of $90,000 over three years. Stanley countered with a proposal that was $8,000-$12,000 more annually, to which USC responded by offering a one-year deal at $96,000. This led Stanley to sue USC for wage discrimination based on gender, and for retaliation.

The Court’s discussion centered around the fact that the men’s coach has greater public relations and promotional responsibilities than the women’s coach and that the men’s basketball team produces 90 times more revenue than the women’s team. Stanley’s qualifications also did not compare favorably to Raveling’s in the eyes of the court, which noted that Raveling had 14 years more experience, was employed by USC three years longer, and that Raveling’s fame (e.g., Raveling authored two books, appeared on national television, and appeared in motion pictures) made him a more valuable asset to USC than Stanley. Thus, this was used as cause for justifying a disparity in pay. Stanley made the argument that much of the increased commercial value of men’s basketball relative to women’s was due to the school’s much larger promotional investment in men’s basketball over women’s basketball. The court stated that this investment was demonstrative of a business decision to allocate resources to the team that generates the most revenue. The Court also stated that the Equal Pay Act does not prohibit wages that reflect market conditions of supply and demand, which may depress wages in jobs mainly held by women. The Circuit Court ultimately granted summary judgment in favor of USC (Stanley v. University of Southern California, 1994).

The case was appealed and reached the Ninth Circuit again in June 1999, when Stanley was coaching at the University of California-Berkley. During the appeal, USC challenged Stanley’s prima facie case under the Equal Pay Act by saying the jobs of the two individuals were significantly different since the men’s coach was responsible for public relations activities, resulting in the men’s team generating 90 times more revenue than the women’s team. The university also claimed there was not a sufficient market for women’s basketball games; thus, Stanley did not have the same pressure to generate revenue as the men’s coach. Stanley countered and stated USC’s prior decisions created the gap between the two basketball programs and could not be relied upon by the university. The Court of Appeals upheld the judgment from the lower court, ruling in favor of the university (Stanley v. University of Southern California, 1999).

Mehus v. Emporia State University

Maxine Mehus, former women’s volleyball coach at Emporia State University (ESU), claimed she was paid less than two of her male counterparts (i.e., men’s basketball coach, women’s basketball coach) despite being tasked with the same type of work. Mehus laid out three specific benefits she did not receive that her male counterparts did. For example, Mehus was provided with a 10-month contract, while the male coaches discussed in this case were provided with 12-month contracts. Mehus was required to teach on top of her coaching responsibilities, while the male coaches were not required to do so. Lastly, Mehus was paid less than the male coaches for equal work that required similar skill, effort, and responsibility. Since Mehus was unable to establish a prima facie case for wage discrimination under the Equal Pay Act, ESU argued the market force defense. However, the defense failed to show evidence of how it determined market value; thus, the courts ruled in favor of Mehus (Mehus v. Emporia State University, 2004).

Fresno State University Triad

Fresno State University (FSU) showed a pattern of gender inequality as it faced three sex discrimination lawsuits, each either lost or settled within a span of just six months. Lindy Vivas, former Fresno State volleyball coach, received a jury verdict of $4.5 million in July 2007 after she was fired in retaliation for advocating gender equity at FSU (Bass, 2016). Vivas was fired in 2004, after leading the volleyball team to its best season in school history. The university stated Vivas was fired for not meeting performance goals and lack of fan attendance at volleyball games (“Fired Fresno State,” 2007).

In October 2007, former FSU Associate Athletic Director Diane Milutinovich settled for $3.5 million in a sex discrimination and retaliation case. Milutinovich said she was forced out of the athletics department because of her gender and for arguing for more opportunities for female athletes at the university (Lipka, 2007). Importantly, settlements do not constitute any admission of wrongdoing. However, the jury verdict just months prior likely created significant leverage for Milutinovich in settlement discussions.

In 2007, former FSU women’s head basketball coach Stacy Johnson-Klein also filed a gender discrimination lawsuit against her employer. Its $19.1 million settlement became the biggest Title IX award at the time. She was terminated as head women’s basketball coach after lodging complaints about gender equity at FSU, which included gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and Title IX violations (“Fired Fresno State,” 2007). Losing the Vivas case and settling the Milutinovich case only harmed the credibility of FSU’s defenses. Johnson-Klein gained popularity during her short tenure as women’s basketball coach at FSU and was responsible for an increase in game attendance. During the trial, Johnson-Klein stated that FSU had a reputation for treating women poorly in its athletic department, and that she endured sexual harassment in order to keep her job. The university’s arguments for firing Johnson-Klein included portraying Johnson-Klein as a manipulator of her players and an allegation that she took painkillers from one of her players. Notably, two of Johnson-Klein’s former players testified on behalf of the university and against their former coach. Fresno appealed the verdict and Johnson-Klein cross-appealed. Ultimately the two sides settled for $9 million (Hostetter & Anteola, 2007).

Potera-Haskins v. Gamble

Montana State University (MSU) fired Robin Potera-Haskins in 2004 after three seasons at the helm of the women’s basketball team. The following year, Potera-Haskins claimed she was fired in retaliation after complaining about gender inequality within the athletic department. She frequently mentioned wage disparity to the athletic director and other senior administrative personnel because the men’s basketball coach was paid 30% more. She also cited the disparity in support for the women’s team compared to the men’s team, which included promotion, publicity, funding, and access to facilities and athletic trainers.

MSU’s defense was that Potera-Haskins’ termination was a result of an abrasive personality that accumulated complaints from players and parents, causing some players to quit. In 2007, Potera-Haskins’ Title VII and First Amendment claims were dismissed, but the court agreed that if her allegations could be proven, a liability suit could be brought under Title IX on a retaliation theory. Ultimately, the courts decided that Potera-Haskins was only entitled to liquidated damages of her early termination, which the school provided to her upon her dismissal (Potera-Haskins v. Gamble, 2007).

Dixon v. Texas Southern University

Surina Dixon, former Texas Southern University (TSU) head women’s basketball coach, sued the university in October 2008 as a result of being terminated just three months after being hired on a one-year contract. She never coached a game for the school. Her offer was for one year with a salary of $75,000. Dixon was told by the athletic director the one-year contract was mandatory until she could prove herself. The men’s basketball coach, a male, was given a five-year contract and a salary twice as much as Dixon’s, both of which were not contingent upon his proving himself. Dixon complained that the wage disparity was a result of discrimination and was dismissed shortly thereafter (Buzuvis, 2010). Dixon was awarded $730,000 in the sex discrimination and retaliation lawsuit (“Former,” 2011).

Miller v. University of Minnesota-Duluth

In December 2014, Shannon Miller, at the time the highest-paid women’s ice hockey coach in the country, was informed that her contract at the University of Minnesota-Duluth would not be renewed. Miller was coming off her fifth NCAA title and maintained a .712 winning percentage in her 16-season tenure. The university’s rationale for this decision was the lack of return on investment. Essentially, the decision was predicated on the women’s ice hockey team not producing enough revenue. Thirteen Minnesota state senators came to Miller’s defense by challenging the university’s decision, inquiring as to why Miller’s counterpart, the men’s ice hockey coach, who had a lower winning percentage and a higher salary, also was not let go (Bass, 2016).

Miller, joined by two other women’s coaches from the university, filed suit in Federal court against the Board of Regents alleging that all three coaches were non-renewed because of their sex and in retaliation for accusing the university of violating Title IX. The three coaches, who openly self-identified as lesbians, also claimed their gender and sexuality led to a hostile work environment and violated the Equal Pay Act. The coaches claimed this same gender- and sexual orientation-based hostile work environment also violated Title VII; however, as this litigation took place prior to the groundbreaking 2020 Supreme Court ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County that extended Title VII protection to sexual orientation, the plaintiffs lost their claim in summary judgment. It appears through the court’s discussion that there is a particularly high threshold to defeat summary judgment on such claims in the Eighth Circuit.

Similar to above cases where women’s coaches attempted to compare their jobs to that of men’s coaches, the court found Miller’s arguments unpersuasive despite the fact that the formal job duties listed in both of their contracts were identical. The fact that Miller inarguably was more successful in terms of winning than her male counterpart was immaterial to the court’s analysis. The court cited the fact that the men’s coach is under more pressure to win and has more demands on his time than the women’s coach. Ultimately, the court dismissed most of Miller’s claims on summary judgment. All claims by the other two coaches were dismissed because they opted not to sign their offered renewals in solidarity with Miller (Miller v. Board of Regents, 2018).

Griesbaum v. University of Iowa

More recently, Tracey Griesbaum, a former University of Iowa women’s field hockey coach, was fired in 2015 based on several player complaints of verbally abusive behavior. This case differs from typical Title IX lawsuits, but at its core, attempts to delve into the double standard females face in the world of athletics, especially in the coaching profession. Parents, spectators, administrators, and others (e.g., fans) oftentimes do not think anything is unusual when male coaches display poor behavior (e.g., curse, get in players’ faces, throw caps, kick chairs, etc.). However, when a female coach exhibits similar behavior, it somehow is an issue. The mindset that male coaches are expected to be aggressive and tough, especially in sports, while women are meant to be nurturing or motherly is long overdue for a change (Hardin & Whiteside, 2012). Many of Griesbaum’s players were outraged after their coach was fired. As a result, four upperclassmen sought to hold the school responsible for Griesbaum’s dismissal. They came to the defense of the coach they agreed to play for because she was tough and pushed them to their limits.

Another coach at Iowa, men’s basketball coach Fran McCaffery, routinely made outbursts in practice and games, including one incident where he crushed a chair and kicked the scorer’s table during a game. He was not disciplined, and Athletic Director Gary Barta, who made the decision to fire Griesbaum, supported McCaffery in his incident. Iowa’s football coach also faced criticism when 13 players were hospitalized after a strenuous workout (Trahan, 2015). An internal investigation found no fault with the head coach or strength coach. The pattern continued at Iowa where five female coaches were terminated in a five-year span. For example, both the men’s and women’s golf coaches were given negative reviews by players, but only the female coach was fired (Trahan, 2015). Griesbaum and her partner, a former associate athletic director at Iowa, both filed lawsuits for gender discrimination against the university, which ultimately ended up settling for $6.5 million (Jordan, 2017).

Moshak and Jennings v. University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee was one of the last Division I institutions to merge its men’s and women’s athletic departments. The consolidation caused 15 people – 12 women and three men – to lose their jobs. Women who previously held leadership positions before the merger no longer held those titles or had those responsibilities. Athletic trainer Jenny Moshak and sports information director Debby Jennings filed two lawsuits, both claiming sex discrimination. Moshak alleged that gender inequity prevented female athletic department personnel from earning equal pay, claiming she was compensated less than her male counterparts either because of her gender or due to her covering women’s sports. Her case was settled in January 2016. Moshak received $375,000 plus attorney’s fees (Bass, 2016).

Discussion

The cases discussed have reasonable claim to seek litigation against the involved institutions. All of the claims stem from feelings of discrimination on the basis of sex, which is an issue presumed to be prohibited under Title IX and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And yet it still happens, not just in sport but also in other professions. Women legally are required to receive equal payment for equal work.

One observation that can be gleaned from all of the cases above is that courts are exceedingly hesitant to side with coaches who were not fired. Schools are similarly hesitant to settle cases with coaches whose contracts they simply did not renew. While it is not established doctrine, it appears that a school can greatly reduce their chances of losing a gender discrimination case if they simply allow the coach’s contract to expire. This puts coaches of women’s teams in a precarious position wherein they essentially have to wait to get fired in order to successfully assert discrimination claims against a university. Most frequently, when coaches of any gender are not renewed, they move on to another job. Most coaches would much rather be coaching than litigating, which likely has allowed many universities to escape scrutiny and costly lawsuits.

Buzuvis (2010) explains the double standards women experience in college athletics, citing many of the aforementioned cases. When Dixon was hired as head women’s basketball coach at TSU, she was offered a lower salary and a shorter contract than her male counterpart, despite being more qualified. Division I women’s volleyball coach Amy Draper maintained in her 2008 lawsuit that the University of Tennessee-Martin held female coaches to a different standard by requiring female coaches to have playing experience along with consistently winning seasons, and that neither of those conditions were expected of male coaches (Buzuvis, 2010). In Griesbaum and Potera-Haskins’ cases, the double standards experienced centered on their coaching styles. They were described in derogatory ways that differ from the nurturing qualities female coaches often are expected to have.

Market Forces

The relative merits of not-for-profit educational institutions using a market forces justification for the massive pay disparity between men’s and women’s team coaches are questionable; however, that discussion is beyond the scope the of this paper. It is inarguable that football and men’s basketball are the largest revenue-driving sports in nearly every NCAA Division I athletic department. The question remains as to whether spending more money on these sports, especially considering the ever-increasing gap relative to women’s sport expenditure, nets a positive return on investment for universities.

Total expenses for men’s sport programs are twice those of women’s sport programs (NCAA, 2017). That disparity widens when you remove scholarship expenditures from the equation and focus solely on operating expenditures. Men’s expenditures account for 67% of total recruiting expenditures, while women’s recruiting accounts for 31%, with 2% unallocated for gender (NCAA, 2017). The disparity gets even larger when you look at coaching salaries with a 70% to 30% split in favor of the men’s coaches, and a 72% to 28% split in favor of the men’s teams as it pertains assistant coaching compensation (NCAA, 2017).

This data allows to reasonably surmise that while Title IX has been effective at providing some equality of scholarship dollars among gender, it has failed to be similarly effective in providing equitable allocation of resources for other expenses. This is despite the fact that Title IX has a provision requiring “equal opportunity,” which specifically lists 10 factors that will be considered when determining whether opportunities are in fact equal (NCAA, 2017). One of the 10 factors is the “assignment and compensation of coaches and tutors” (NCAA, 2017). However, a disparity in one of these areas can be offset by a perceived benefit of another.

That being stated, there is research to support the notion that spending more money on football and men’s basketball will result in more revenue. Colbert and Eckard (2015) concluded that paying a Division I FBS football coach more was positively correlated to increased team performance, but recognizes diminishing returns at a certain point. Chung (2017) concluded that wins in football and men’s basketball is correlated with revenue growth in an athletic department. This particularly is true if a team wins a national football championship, as there is roughly an 11% revenue increase the following year (Smith, 2017). Nonetheless, spending money in hopes of winning a national football championship often does not yield the return on investment. Since its inception in the 2014-2015 season, the College Football Playoff (CFP) has featured the top four ranked teams at the conclusion of the regular season, which equates to 28 total participants over the seven years of its existence. Of the 28 participants, only 11 have been unique universities. The most recent iteration in 2020 featured the University of Alabama, Clemson University, Ohio State University, and the University of Notre Dame. Each of these teams had participated at least once before, with Alabama and Clemson both appearing six times and Ohio State appearing four times (Coleman, 2021).

It should be noted that paying a head coach more does not always factor into the university finishing in the top four of the CFP ranking. The University of Michigan and Texas A&M University, for example, have never made the CFP playoff despite their coaches’ salaries ranking fourth and fifth highest in the NCAA, respectively (NCAA Salaries, 2021). Further, many of these universities have massive revenue guarantees regardless of how many games they win. For example, the Power 5 conferences have lucrative television deals split evenly among their member institutions. Southeastern Conference (SEC) broadcast rights are especially lucrative, as each of its members earned more than $45 million for the 2019 fiscal year. In 2020 the SEC received a new television rights deal from Disney’s ESPN that will pay the conference $300 million annually, which is a substantial increase from the $55 million the conference made from CBS in a previous partnership (Myerberg, 2020).

The prevailing notion is that money is spent on men’s sports because football and men’s basketball bring in massive amounts of revenue. While this can be the case, it is not always true. For example, the University of Connecticut (UConn) submitted a report to the NCAA regarding its 2018 season that stated every sport at operated at a loss. This includes what is widely regarded as the most successful women’s basketball program in the country, which operated at a $3.1 million loss. However, the men’s basketball team lost $5 million, and the football program lost more than $8 million (Bigelow, 2019). While UConn women’s basketball coach Geno Auriemma is the highest-paid women’s coach in the NCAA, he makes roughly $1 million less than men’s coach Dan Hurley. This is just one example of a university trying to achieve success in the “high revenue producing” sports only to be unsuccessful. Interestingly, UConn’s athletic department operates at a $40 million deficit annually, which is subsidized by student fees and institutional support (Bigelow, 2019).

The question begs to be asked as to whether it is still necessary for high-level spending on these sports in order to attempt to turn a profit in revenue, or if men’s college athletics have hit a tipping point. The major conferences disburse tens of millions of dollars to each of their member institutions as a result of large television broadcasting deals. That money is paid out regardless of the salaries given to their coaches. The mid-major conferences, like the American Athletic Conference (AAC), of which UConn was a member until 2019, pay coaches in the high six to low seven figures annually and still fail to turn a profit. Orszag and Orszag (2005) indicated that an extra dollar in operational spending on football and men’s basketball in athletic departments is related to only a one dollar increase in operating revenue in the medium-term, meaning that extra dollar of spending is a net zero investment. Whether that dollar would be better invested in women’s sport is currently unknown. There are few examples of major capital investment into women’s collegiate athletics nearing the scale that is invested in the men’s programs, despite indications that women’s collegiate basketball is rising in popularity.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, ticket demand for women’s regular season basketball games was on the rise and outpacing the demand for men’s tickets in some circumstances (Higgins, 2021). While the NCAA insists their women’s basketball tournament loses money, sports economists estimate that women’s basketball brings in nearly a billion dollars in annual revenue. The 2019 women’s championship game boasted more than 3.68 million viewers (Shea, 2021). While that pales in comparison to the 19 million viewers that watched the men’s tournament, the women’s tournament championship viewership is comparable to other profitable sports broadcasts, such as Game 1 of Major League Baseball’s 2019 National League Divisional Series and a Men’s Wimbledon final (Shea, 2021). Disney’s ESPN, which airs the women’s tournament, has sold advertisement time to a number of large brands such as Bounty, Crest, Chevron, and Dodge. The tournament also added 17 new sponsors from the prior year (Jenkins, 2021). Further, an analysis of the social media followings of men’s and women’s basketball players on the final eight teams left in their respective tournament shows that eight of the 10 most-followed athletes are women, including the top two (Baker, 2021).

Future Implications: Paycheck Fairness Act

During now-U.S. President Joe Biden’s campaign for office, he ran on a platform that included gender equality as a top priority for his administration. Within the first 75 days as President, he established a White House Gender Policy Council via executive order in March 2021. It is now possible, if not likely, that new legislation will be passed in order to help women in all industries, including collegiate athletics, combat the gender pay gap. An example of such a law is the Paycheck Fairness Act. The Paycheck Fairness Act (H.R. 7), sponsored by Representative Rose DeLauro (D-CT), was introduced to the 117th Congress in January 2021 and boasts 225 cosponsors. The legislation proposes amendments to help strengthen the Equal Pay Act. Most notably, it changes the language of a defense that allows an employer to claim that the disparity is based on any other factor than sex, to more strict language requiring a bona fide, job-related factor. While it is progress, this language is unlikely to help coaches of women’s teams overcome the litany of case law and public opinion that claims their jobs are not sufficiently equal to their male counterparts, thereby justifying the disparity in pay. The bill also calls for the Department of Labor to establish a grant program aimed at developing negotiation skills for girls and women, and to conduct studies to eliminate pay disparities among the sexes.

Like any bill proposal, the Paycheck Fairness Act faces long odds of being signed into law. While the stricter language potentially could make it more difficult for universities to explain and justify some of the disparities in coaches pay, many claims will face the same obstacles that previous claims have faced. Namely, the disparity is not based on the gender of the coach, but rather the gender of the athletes that they coach. This issue is more suited for a Title IX claim, particularly with the provision regarding equal opportunity among genders and specifying the compensation of coaches as a factor. However, as the case summaries indicate, Title IX has been a relatively ineffective tool in combatting the problem. As Title IX is enforced by the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights, the interpretation of the law can vary greatly from administration to administration. It will be worth watching recently confirmed Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona and his administration’s treatment of Title IX. They could potentially take a harder line stance on pay disparities among coaches, but as the law is a civil statute and not actively policed, it will require a specific Title IX claim to see if the interpretations regarding equal opportunities will be stricter.

Conclusion

The basis for gender discrimination and equal pay come from the Equal Pay Act and Title IX. Both prohibit employers from paying employees different wages for similar work. However, in athletics many variables come into play when examining the pay gap, especially in coaching. Athletic departments can argue that coaches with higher salaries are paid as such based on greater job responsibilities due to larger rosters, bigger budgets, or greater travel obligations. Other factors such as experience level and market value also may play a part in the decision to compensate one coach more than another. However, it is clear that women not only desire to be high-level sport leaders as coaches and administrators, but also are capable of such. Gaining a better understanding of how women experience discrimination as intercollegiate athletic employees would help universities strive for gender equality and better reflect society. Promoting women into positions of power, along with equal pay and the absence of gender discrimination, would help the sport profession and the NCAA close the gender gap and reach its goal of gender equity within the collegiate sport space.

References

AAUW. (2018). The simple truth about the gender pay gap. https://www.aauw.org/research/the-simple-truth-about-the-gender-pay-gap/

Acosta, R. V., & Carpenter, L. J. (2014). Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal, national study. Thirty-seven year update, 1977-2014. http://www.acostacarpenter.org/2014%20Status%20of%20Women%20in%20Intercollegiate%20Sport%20-37%20Year%20Update%20-%201977-2014%20.pdf

Asher, M. (2000, September 25). Tyler sues Howard for $105 million. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/2000/09/25/tyler-sues-howard-for-105-million/4a80b681-5cde-4955-9989-6b4899203de8/

Baker, K. (2021, March 29). Eight of the 10 most-followed NCAA Elite 8 basketball players are

women. Axios News. https://www.axios.com/ncaa-basketball-social-media-followings-a98b2f21-e907-4276-b860-32565654d64a.html

Barrett, J., Pike, A., and Mazerolle, S. (2018). A phenomenological approach: Understanding the experiences of female athletic trainers providing medical care to male sports teams. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training, 23(3), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijatt.2017-0032

Bass, P. (2016). Second generation gender bias in college coaching: Can the law reach that far? Marquette Sports Law Review, 26(2), 671-711. http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol26/iss2/16

Bigelow, S. (2019, January 22). Analysis: Are big-time UConn sports worth the money? AP News. https://apnews.com/article/638e8796785041e490be3242b9946da7

Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 US (2020). https://www.oyez.org/cases/2019/17-1618

Buzuvis, E. E. (2010). Sidelined: Title IX retaliation cases and women’s leadership in college athletics. Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy, 17(1), 1-45.

Chamberlain, E., Cornett, H., & Yohanan, A. (2018). Athletics & Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 19, 231-263.

Chung, D. J. (2017). How much is a win worth? An application to intercollegiate athletics.

Management Science 63(2), 548-565. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2337

Cloninger, D. (2016, April 1). South Carolina extends Frank Martin’s contract through 2022. The State. https://www.thestate.com/sports/college/university-of-south-carolina/usc-mens-basketball/article69446227.html

Cloninger, D. (2015, June 19). Staley first USC women’s coach to earn $1 million per year. The State. https://www.thestate.com/sports/college/university-of-south-carolina/usc-womens-basketball/article24969238.html

Colbert, G. J., & Eckard, E. W. (2013). Do colleges get what they pay for? Evidence on football

coach pay and team performance. Journal of Sport Economics. 16(4), 335-352. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1527002513501679

Coleman, M. (2021, January 1). Who has the most college football playoff appearances?

Clemson, Alabama are tied. Sports Illustrated. https://www.si.com/college/2021/01/01/college-football-playoff-history-most-appearances

Deli v. University of Minnesota, 863 F. Supp. 958(D. Minn. 1994). https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/863/958/1459805/

Doyle, P. (2017, March 10). Auriemma, Ollie under contract at UConn through 2021 for close to $31M. Hartford Courant. http://www.courant.com/sports/uconn-womens-basketball/hc-uconn-basketball-coaches-contracts-0310-20170309-story.html

Equal Pay Act. (2017, November 30). History.com.

Fenton, A. (1998). Compensation issues in coaching of women’s amateur sports: A study of the legal precedents and an evaluation of three methods of relief. Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, 8(3), 124-140.

Fired Fresno State coach wins $19M in sex-discrimination lawsuit. (2007, December 6). The Fresno Bee. http://www.csun.edu/pubrels/clips/Dec07/12-07-07K.pdf

Fired women’s basketball coach files $105 million suit against Howard University. (2000, October 12). DiverseEducation.com. https://diverseeducation.com/article/895/

Former TSU hoops coach wins $730,000 for sex bias. (2011, November 20). Business Management Daily. https://www.businessmanagementdaily.com/20376/former-tsu-hoops-coach-wins-730000-for-sex-bias/

Gentry, J. K., & Alexander, R. M. (2012, April 2). Pay for women’s basketball coaches lags far behind that of men’s coaches. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/sports/ncaabasketball/pay-for-womens-basketball-coaches-lags-far-behind-mens-coaches.html

Higgins, L. (2021, March 19). Women’s March Madness is growing in popularity — and

undervalued. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/march-madness-womens-college-basketball-ncaa-tournament-11616155596

Hostetter, G., & Anteola, B. J. (2007). Jury says CSUF discriminated against Stacy Johnson-Klein. The Fresno Bee. http://www.csun.edu/pubrels/clips/Dec07/12-07-07K.pdf

Jenkins, S. (2021, March 24). The NCAA’s shell game is the real women’s basketball scandal.

The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/03/25/ncaa-women-basketball-tournament-revenue/

Jordan, E. (2017, March 19). University of Iowa pays $6.5 million in Meyer, Griesbaum cases. The Gazette. https://www.thegazette.com/sports/university-of-iowa-pays-6-5-million-in-meyer-griesbaum-cases/

Lapchick, R. (2019, February 27). The 2018 racial and gender report card: College sport. The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. https://www.tidesport.org/racial-gender-report-card

Lipka, S. (2007, August 3). Fresno State grapples with a spate of sex-discriminationclaims. The Chronicle of Higher Education: Athletics. http://chronicle.com/weekly/v53/i48/48a02901.htm

Mehus v. Emporia State University, 326 F. Supp. 2d 1213 (D. Kan. 2004). https://casetext.com/case/mehus-v-emporia-state-university-7

Miller v. Board of Regents of the University of Minnesota, No. 15-CV-370 (D. Minn. Feb. 1, 2018). https://casetext.com/case/miller-v-bd-of-regents-of-the-univ-of-minn

Myerberg, P. (2020, December 10). Analysis: New ESPN/ABC TV deal will give SEC even

more resources to dominate college sports. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/ncaaf/sec/2020/12/10/sec-contract-abc-espn-gives-league-more-resources-dominate/3884360001/

NCAA. (2020). 2020-21 NCAA Division I Manual. https://www.ncaapublications.com/p-4605-2020-2021-ncaa-division-i-manual.aspx

NCAA. (2017). 45 years of Title IX: The status of women in intercollegiate athletics. https://www.ncaapublications.com/p-4510-45-years-of-title-ix.aspx

NCAA Salaries (2021, March 31). Top NCAAF coach pay. USA Today. https://sports.usatoday.com/ncaa/salaries/

Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance, 34 C.F.R. § 106 (2000). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-34/subtitle-B/chapter-I/part-106?toc=1

North Haven Board of Education v. Bell, 456 US 512 (1982). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1981/80-986

Orszag, J. M., & Orszag, P. R. (2005). The empirical effects of collegiate athletics: An update. NCAA.http://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/RES_EmpiricalEffectsOfCollegiateAthleticsUpdate.pdf

Potera-Haskins v. Gamble, 519 F. Supp. 2d 1110 (D. Mont. 2007). https://casetext.com/case/potera-haskins-v-gamble

Shea, B. (2021, March 9). NCAA’s March Madness is set to return, but will the TV audience

come back too? The Athletic. https://theathletic.com/2438092/2021/03/09/march-madness-ncaa-tournament-ratings-tv/#:~:text=The%202019%20tournament%20averaged%2010.9,according%20to%20Sports%20Business%20Daily.

Smith, C. (2017, January 11). The money on the line in the college football national

championship game. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/chrissmith/2017/01/09/the-money-on-the-line-in-the-college-football-national-championship-game/?sh=622977a22777

Stanley v. University of Southern California. 13 F.3d 1313 (9th Cir. 1994). https://casetext.com/case/stanley-v-university-of-southern-california

Stanley v. University of Southern California. Nos. 95-55466, 95-56250, 96-55004 (9th Cir. 1999). https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-9th-circuit/1142433.html

Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, 20 U.S.C. §§1681 – 1688 (2018). https://www.justice.gov/crt/title-ix-education-amendments-1972

Trahan, K. (2015, February 16). The gender discrimination lawsuit that could change college sports forever. Vice Sports. https://sports.vice.com/en_us/article/gv7evx/the-gender-discrimination-lawsuit-that-could-change-college-sports-forever

Tyler v. Howard University, No. 91-CA11239 (D.C. Super. Ct. 1993).

Wage and Hour Division. (n.d.). Handy reference guide to the Fair Labor Standards Act. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/hrg.htm

Walters, J. (2016, June 02). Taking a closer look at the gender pay gap in sports. Newsweek. www.newsweek.com/womens-soccer-suit-underscores-sports-gender-pay-gap-443137

Weatherford, G. M., Wagner, F. L., & Block, B. A. (2018). The complexity of sport: Universal challenges and their impact on women in sport. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 26(2), 89-98. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2018-0001