By Dr. Camille Kraft

Nothing grabs the headlines firmer than a story of a player who is caught with an illegal substance. Megastar-athletes Josh Gordon and Randy Gregory have recently joined the long and infamous list of such fallen athletes. Both players were trapped in the hands of illegal substance usage while playing in the N.F.L. and were suspended multiple times. Josh Gordon “has been suspended eight times by either his team or the N.F.L.” (Barry Wilner, AP June 19, 2020) and Randy Gregory has been suspended at least four times for his “marijuana addiction based on self-medicating his bipolar disorder.” (K.D. Drummond June 9, 2020). These young men experienced humiliation and isolation as a result of being removed from their job, their income, and their teammates. These were the consequences of the previous N.F.L. Substances of Abuse (SOA) Policy and Program.

In March 2020, as part of the new collective bargaining agreement, the N.F.L. and players union updated its SOA Policy by, among other things, eliminating suspensions for marijuana misuse. When this was first rumored, I immediately thought the SOA Policy had been weakened, so much so, it appeared as though I thought it would be the end of the Policy altogether. However, after studying the new Policy, I began to understand why it appeared softer as it aligned itself with the new marijuana laws in a majority of U.S. states. As of July 2020, marijuana usage is illegal in only eight states (16 percent) across America, and only two of which (Wisconsin and Tennessee) have N.F.L. teams. In contrast, 11 states (22 percent) in which 10 of the 32 teams reside have fully legalized marijuana usage. The remaining 31 States (62 percent) have allowances for marijuana usage, which means 30 teams operate in states that have decriminalized marijuana to some degree.

2020 Marijuana Usage

Illegal 8 states 16 % of U.S. 2 NFL Teams

Fully legalized 11 states 22% of U.S. 10 NFL Teams

Allowance 31 states 62% of U.S. 20 NFL Teams

“What is most notably unique about the new SOA Policy is the elimination of suspensions for marijuana misuse and the significant impact they may have on both Gordon and Gregory.”

In addition to the increase allowances for marijuana usage, the N.F.L. has also started to listen to the players’ requests to use marijuana as a natural alternative to opioids for pain relief and to avoid possible addiction.

“Medicinal use of marijuana has had some proven success in multiple studies and, of course, anecdotally by former players. The legislative traction mentioned above certainly did not come without state legislatures vetting ‘the science,’ especially juxtaposed against the long-term dangers of opioids, the traditional and accepted form of pain management by NFL teams.”

“We’ve seen many N.F.L. players advocate for the use of marijuana—Eugene Monroe, Jake Plummer and Ricky Williams were among the first, now Chris Long, Kyle Turley and David Irving more recently. It will be interesting to see if their words are heeded by the N.F.L. and N.F.L. Players Association in their deliberations, both on the committee level and in future bargaining. I see potential for promising results but temper my enthusiasm and have doubts as to whether the league is prepared for further.”

The NFL’s Stance on Marijuana is Adapting, But Major Changes Will Come Slowly Plus, a quick thought on Bart Starr and his legacy in Green Bay. ANDREW BRANDT, MAY 28, 2019

For simplification, one can think the SOA Policy as the playbook and the Intervention Program as the coach: The Vince Lombardi of patient care – tough but fair. Due to its structure and practices, the Intervention Program, within the SOA Policy, is often referred to as punitive, yet surprisingly, it has many redeeming qualities that are often overlooked. In fact, the N.F.L. offers what some might consider the Rolls-Royce, or best practices, of providing premier care for substance usage within the world of professional sports. Together, the N.F.L. and the N.F.L.P.A. are responsible for funding the Intervention Program, which is comprised of administration, staff, specialized clinicians as well as case workers, and liaisons. This group of specialists regularly confers with experts and treatment centers throughout the country within the addiction community and together, have formed a very sophisticated intervention program.

The SOA Policy is a collective effort of the League, the Player’s Association and current players contributions most recently resulting in a 10-year labor deal, which narrowly passed with a 1,019-959 vote. The revised SOA Policy is a 36-page document chock-full of legal language outlining the behaviors and expectations of those who are found to be using banned substances while playing in the N.F.L. (https://nflpa.com/active-players/drug-policies.)

Dully noted, the most titillating and highly debated modification to the SOA Policy is the removal of suspensions for marijuana misuse. Although this amendment reduces suspensions and benefits teams by allowing for a more consistent roster throughout the season, not everyone agrees with it. Bears’ Allen Robinson blasts approval of new NFL CBA (Skyler Carlin, March 15, 2020). With the new admission of marijuana usage, one would think the SOA Policy has lost its integrity. However, after closer review, one realizes that the players’ well-being remains of paramount importance, despite the amendments. For example, the original admittance standards into the Intervention Program remain the same: positive test results, behavior, or self-referral (Bylaw 1.4.1, p.11). A player is also admitted into the Intervention Program should he have a prior to or known difficulty with a certain substance before joining the N.F.L.

“However, if a player enters the NFL with a confirmed history of drug or alcohol issues, he is then implemented into the NFL’s anonymous substance abuse program. While in the program, that player can be tested at random at any given point throughout the year no matter where they are in the country.” Bleacher’s Report Insider’s Perspective on NFL Drug Tests, RYAN RIDDLE, JUNE 11, 2013

Tests are ongoing year-round. For instance, players are tested during the annual Combines in February as well as in the off-season. What has been altered is the time in which players are tested during the season and the duration of the testing time. For example, the former Policy annually tested all players under contract for four months (April 20 through August 9), whereas the new Policy requires players to be tested during training camps which is a two-week period. This translates to players have a smaller window in which they are randomly tested for illegal substance usage. However, they are still required to be tested. The results of these tests continue to be analyzed for illegal substances and therapeutic use exemptions (TUEs) for attention deficit and attention deficit disorders, diuretics in the treatment for hypertension, as well as hypogonadism.

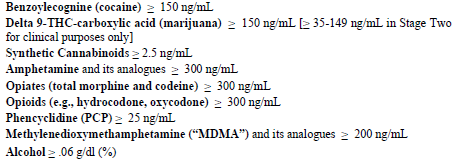

Should a player test positive for these substances, they will receive notification explaining they have been placed into the Intervention Program (Bylaw 1.3, p.7). The Intervention Program is coordinated by an independent contractor (the administrator of the SOA Policy) who arranges and coordinates all aspects of player care at the direction of the medical director. The type of care which the player will receive is determined by both the medical advisor as well as the medical director. The medical advisor primarily oversees the player sampling, while the medical director coordinates and oversees player (patient) care, including whether a player is placed into either Stage 1 or Stage 2, how long he should stay in either stage, and whether they should advance to the next stage.

The majority of players who test positive for banned substances generally begin their journey in Stage 1 (Bylaw 1.5.1, p.12). Stage 1 is more or less a 60-day holding period designed to curb inappropriate substance misuse and/or behavior. This stint affords players the opportunity to demonstrate their ability to remain substance-free by consistently providing negative test results, which allows the player to remain in complete control of his destiny. Should their urine test return free of substances, the medical director may release the player from the observational portion of the program.

However, if the player does not remain substance free, then more than likely, he is placed into Stage 2 of the program. In Stage 2, (Bylaw 1.5.2, p.13) the level of monitoring intensifies, focusing on providing customized treatment plans for the player. This may involve any and all combinations of unannounced urine testing, a treatment plan, a case manager, a clinician, and possible treatment center (inpatient or outpatient care) which rests on the collective assessment of the player’s severity of needs.

Once the assessment has been made, a course of action is outlined in the form of a treatment plan, which serves as a contract that clearly outlines the player’s expected behaviors and level of commitment that he must follow. This contract may be as comprehensive as requiring the player to attend a 12-step program, as well as counseling sessions, all while continuing to provide samples during unannounced tests. The testing process involves providing observed urine samples to an assigned tester. As soon as the player has been notified that they will be tested, they have a prescribed amount of time in which they must make themselves available. Should a player fail to take part in the test, he is considered a no-show which then results in a positive test.

Prior to the introduction of the 2020 SOA program, each player in the program could potentially be randomly tested up to a maximum of 10 times per month. Under the current Policy, the number of times in which a player is tested is at the discretion of the medical advisor. These tests often serve as a guide for the medical director, case manager, as well as the clinician, who must decide how to manage the player’s care. For instance, the player’s sample can expose what chemical was ingested, at what level and how often. The results of these tests reveal whether the player is continuing to misuse substances, as well as additional drugs. These results are used to guide the medical director’s decisions regarding duration within the Intervention Program and complexity of assistance that is needed.

Players are mostly compliant while they are in Stage 2 because they want return to the field so they can be paid. Unfortunately, there are a few outliers who continue to garner public notoriety by continuing to recklessly consume illegal substances and disregarding their accountability to both the N.F.L., as well as their teammates. For these men, the N.F.L. asserts its authority by enforcing Policy bylaws, such as garnishing salaries. This behavior ultimately can extend a player’s time within the Intervention Program under heightened scrutiny (Bylaw 1.5.2 (c), p.14).

As in year’s past, the new Policy allows players to appeal their penalties. For example, a player may have ingested large amounts of water due to heat, unknowingly needing to provide a tester with a urine sample. Should a player’s test results be determined to be diluted, a player would most likely appeal their results. Whatever the cause, the Policy has allowances for players to an appeal which may lead to a hearing. Players wishing to seek an appeal and hearing should consult pages 15-23 of the Policy, which outlines clear directives on how to proceed.

Clarification and ease seem to compliment the 2020-2030 SOA Policy which seem to deliver a more current or refreshed set of standards. What was once cumbersome, and confusing has become slightly less dreary. Typically, policies are tedious and usually difficult to navigate. The new N.F.L. SOA Policy has reduced the burden with improved appendices. The comprehensive list has doubled in number with the redistribution of four topics that were previously buried within the Policy. These topics have morphed into four new appendices D, E, F and G which are easy to read and understand. As a result of this information reshuffling, the Policy instantly has become “user friendly” not only for players, but for agents, wives, girlfriends, parents, and so on.

A. Procedures for Dilute Specimens

B. Procedures for Reinstatement Following Banishment

C. Policy Personnel – Contact Information

D. Abuse of Prescription and Over-The-Counter Drugs (New)

E. Procedures for Failure to Appear for Testing (New)

F. Therapeutic Use Exemptions (New)

G. Permitted Activities for Suspended Players (New)

Let’s say a player tests positive for an over the counter drug. In years past, he would have had to have read through the Policy and try to make sense of the necessary steps to take. Whereas the new Policy clearly outlines these steps in Appendix D and eliminates confusing rhetoric. The same thinking can be applied to the remaining three appendices. For instance, a new agent may have a client who missed a drug test. All they would need to do is simply turn to Appendix E and follow the outlined procedure. Appendix F speaks directly to therapeutic drugs. And lastly, Appendix G, in my opinion, is the most forward-thinking procedure of all – Permitted Activities for Suspended Players. This portion of the new Policy makes absolute sense. I have always been exceedingly concerned about both the injured and the suspended player. In years past, I have watched athletes become vulnerable when they are suddenly removed from their team. In addition to becoming isolated and invisible, these players are also most likely facing an unstructured schedule for the first time in their lives. During this experience, they can lose their identity which can lead to depression. Depression then has the potential to lead to substance abuse. This predicament can become troublesome, leaving players susceptible to making more poor decisions given their unsupervised and detached circumstance. Thus, being suspended can create a vicious self-destructive cycle. Therefore, I am in full support of Appendix G which allows suspended players to remain within their daily rituals and support groups. This new approach provides the opportunity for these players to learn new coping skills during their suspension by enabling them to adapt to changes and transitions. Most importantly, the new Policy offers players security in knowing that there is a structured system for them should they face the effects of substance misuse.

With such a robust and well-thought-out Policy, the N.F.L. has a unique ability to use its brand to influence and normalize contemporary drug-related conversations. The League can potentially, influence others and change lives for the better, by tackling such topics as opioid addiction and mental health support. Data from 2018 from the National Institute of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Advancing Addiction Science, shows that every day, 128 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids.1 The misuse of and addiction to opioids—including prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—is a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare.

- Roughly 21 to 29 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them.6

- Between 8 and 12 percent develop an opioid use disorder.6

- An estimated 4 to 6 percent who misuse prescription opioids transition to heroin.7–9

- About 80 percent of people who use heroin first misused prescription opioids.7

And bravo to the players who have already championed the discussion to include mental health awareness. They have created a movement. At the request of Martavius Bryant and Matthew Marciz, there are efforts being made to ensure mental health assistance is provided to all N.F.L. players.

There was some debate as to whose responsibility this is when I wrote about that topic, but the bottom line is that it is in the league’s own best interest to return these Players to the field. It’s not good for them for their on-field product or for their public relations to make headlines about Players being suspended, and then follow-ups about how their lives went off the rails afterward.

(NFL Requiring Teams to Hire Mental Health Experts Starting In 2019 To Work with Players by Matthew Marczi Posted on May 26, 2019 at 1:00 pm)

Bryant said Monday that he has been seeking league approval to see a counselor near his home in Las Vegas with whom he has had success in the past. The league has instructed him to fly to Chicago to visit NFL medical director Richard Spatafora for a status update and to gain NFL approval for treatment from his Las Vegas-based counselor. To this point, Bryant said, the league has permitted him to seek treatment from only its network of counselors.

Suspended WR Bryant to apply for reinstatement (May 6, 2019, Dan Graziano, ESPN Staff Writer)

Although the SOA has recently undergone revisions to become more player-friendly, it still lacks a comprehensive safety net for substance misusers. In other words, for a player to fully exhaust the SOA’s maximum potential, one would have to demonstrate proficient self-awareness. For this specific population, I find this expectation to be highly unlikely and almost culturally impossible because counseling is diametrically opposed to athletic teachings. These teachings often include mantras such as “never show your emotions”. Such catchphrases have been ingrained into athletes their entire life, thus, the unpacking these lifelong lessons takes substantial work. An elite athlete has little room within their craft for processing their individual thoughts. Most likely, he or she has been conditioned with repetition and choreographed plays, making the therapy process counterintuitive. Therefore, when working with clients, I often compare the introduction to therapy to being thrown into a swimming pool with the expectation to swim. So, just as a good lawyer prepares his client for court, I strongly believe there is a need to prepare people, especially elite athletes, for therapy. By developing their counseling muscle, so to speak, we can shorten the bridge between athletics and treatment so that they can effectively and efficiently return to their lives. Hence, I strongly recommend that athletes be required to develop counseling skills. Counseling and mantras are not designed to cancel each other out but rather enhance one another.

Leaving these young men in vulnerable situations is irresponsible and a significant part of the continual cycle of N.F.L. employment suicide. In addition, to developing counseling skills, reviewing the SOA Policy on an ongoing basis would afford players an advantage as well. Although both practices are unpopular, philosophically, being prepared for all outcomes is what coaches and players do naturally. Not engaging in the SOA Policy or counseling would be like providing an athlete a state-of-the-art training room yet never teaching them exactly how to use the equipment.

Unfortunately, no matter how many revisions are made to the SOA, what remains constant is that players will continue to fall from grace at the hands of substance misuse as sure as the sun will rise and set. Nevertheless, the cycle is breakable, and the tools are available to stop these self-destructive outcomes. Players have access to the N.F.L. SOA program and its intervention program. Together, I believe, they are the standard for providing support for players with the intent of reducing substance misuse and returning players to their craft. What is missing is the preparation for the counseling experience and the allowance for the development of self-awareness proficiency. Therefore, my suggestion would be to saturate players with both the SOA Policy and counseling skills proficiency assessments with the intent of stopping the cycle of self-destruction. In summary, the 2020-2030 N.F.L. SOA Policy is a strong mechanism to guide players, discourage behaviors and provide support. Where the Policy may fall short is that Players are placed into the intervention process rather than themselves seeking help. Keep in mind, the Policy is not designed to “cure” players of their behaviors, but rather, it is intended to provide player with the opportunity to remain safe while playing football. My concerns are for the player who continues to misuse substances, is not suspended, and loses a large portion of his earnings. What is the resolution for this player and what toll will this take on his well-being? I also have concerns for players who remain healthy but are at the risk of losing their career at the hands of the player who is supposed to be performing at an elite level but is hindered by his addiction.

Kraft is the former Administrator of the N.F.L. Substances of Abuse Program, a longtime college administrator and a consultant. (College Student-Athlete, Westmont College, MS- Athletic Counseling, Springfield College, MA, EdD- Leadership and Administration in Higher Education, USC.)